More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

“There’s only one way to tackle life, enjoy a day at beach, and jump into a Great Lake: Headfirst!”: 'LAKES' to 'LAYOUT', how lake areas transformed into residential & commercial entities, educational institutes, bus stands, stadiums etc. and at what cost

Bengaluru: How many lakes do you think there are in Bengaluru? One hundred? Five hundred? A thousand?

|

Bangalore’s Disappearing Lakes maps the centrality of water in the city’s physical and spiritual landscapes, and how these landscapes are historically connected. Prepared for Guerrilla Cartography's Water Atlas, the map combines three information layers, which are often separated in maps of water scarcity, to describe changes in an urban landscape that was once rich with water but is now under the huge pressures of climate change and population growth. These layers are landcover change, vanished and compromised lakewater, and religious processions that celebrate a city once boasting a “necklace of lakes.” Together, these three layers track an existential rewriting of human relations to water.

The rainwater-dependent lakes, built in the sixteenth century, were long a basis for neighborhoods and were maintained by resident custodians who inherited the office. Minimal urban oversight or regulation on development, however, encouraged an over-paved city, compromising the often-seasonal network of lakes, which were formerly connected by underground canals in an artificial watershed, and removed them from groundwater recharge. Bangalore’s rapid expansion has challenged local hopes for environmental restoration of walled tanks and miniature reservoirs, which began in the early 2000s. A crisis of drinking water, the stench of refuse, and industrial pollutants place problems of local restoration on Bangaloreans’ front plate.

Modern Bengaluru (aka Bangalore) today faces many forms of water stress — soil subsidence, water pollution, flooding of residential neighborhoods, poor infrastructure, and difficulties with water distribution. Poor environmental safeguards have let surviving lakes foam over with industrial byproducts that rise onto their surfaces or combust in flames, and their catchments are greatly contracted by residential expansion and landcover change. Still, it remains difficult to obtain accurate public data on the purity of water or water safety, the precarity of drinking water supplies, and groundwater and urban pollution.

|

In the context of a broad crisis in groundwater supplies across India — Bengaluru, Delhi, Chennai, and Hyderabad are poised to exhaust water supplies by 2020 — the lost landscape of lakes poses poignant problems in this plateau city removed from rivers, whose early rulers long relied on tanks to harvest water for agriculture. Most of the larger lakes exist outside the city center, and most of those are polluted by untreated sewage or industrial run-off.

“Bangalore’s Disappearing Lakes” maps the filled-in and polluted tanks used for rainwater harvesting (each shown by a marker evoking mourning of their loss) against a ritual procession, called the Karaga, which links sites of traditional tanks in the increasingly paved center of this South Asian megacity. The lakes orient the Bengaluru Karaga procession, held each year at the first full moon of the Hindu calendar. The procession links a religious diversity of Hinduism in Karnataka Province — including Bhakti and Vedanta Hinduism — with Muslims, Buddhists, Jains, Thigala, and Christians. This urban ceremony transcends religious divides by uniting the city around a shared symbolism, tapping public memory of past geography of lakes that recalls a lost centrality of water in the city, of lakes long used by cleaning people, for laundry washing, and by fishermen. Will this ritual survive the encroachment or disappearance of once-healthy water bodies and paving of lakebeds?

With urban development, the paving of lakes in central Bengaluru transformed a landscape rich with water into one threatened by flooding, pollution, and disrupted ecosystems. The crisis of water created by limited groundwater compromised urban residents’ historical relation to an interlinked system of lakes that now regularly overflow, shrink to bogs clotted with weeds, and where flammable industrial runoff regularly catches fire.

|

For a city famed for its many water bodies, often for the wrong reasons, with lakes spewing fire and noxious foam, there is a lack of reliable records about Bengaluru's vital blue infrastructure.

This data gap has significant impacts on the ground. For instance, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) recently resumed construction of a road within the buffer zone of the Pattandur Agrahara Lake near Whitefield in the eastern part of the city. Citizens' groups have been fighting to protect the lake, said to be nearly 1,000 years old, while the BBMP claims that they can build in the area as they are not breaking any law.

The BBMP and the district administration both do not have a survey map of the lake, they told the Deccan Herald in December 2021.

Multiple groups--including citizens groups and eight government agencies--manage Bengaluru's lakes. Yet, there is no comprehensive or up-to-date database of the lakes.

This is despite lakes acting as buffers during floods, providing livelihood to fishermen and livestock owners, and providing habitat to various fauna. There are many instances of Bengaluru's loss of water bodies to encroachment, degradation, shrinking or flooding, causing ecological, social , and economic damage.

We reached out to the BBMP for information on the Pattandur Agrahara Lake, the number and most recent database of Bengaluru's lake, and whether there is a plan to better map the city's lakes. We will update the story when we receive a response.

To protect existing lakes, the key is to first document them and then ensure that these data are publicly accessible. A crowdsourcing initiative, by the Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation (CSEI) at ATREE, a research institute based in Bengaluru, has identified 1,350 lakes spread across Bengaluru.

Gap in data on Bengaluru's lakes

Lakes in Bengaluru were originally built for irrigation and drinking water purposes. As a result, they were governed by local communities who used them as a common pool resource. But, over the years, the lakes have come to be managed by government agencies and the nature of rules governing the lakes have become more formal and uniform.

Given the complex history of governance and stewardship on Bengaluru's lakes, as we said, there is no comprehensive and up-to-date database of the lakes. The public datasets released by government agencies have been created using information from various agencies over the years. These datasets are incomplete and often inaccurate as either multiple lakes are missing or have been marked inaccurately.

| Agency | Key Responsibilities |

| Citizen lake groups | Activism, maintenance, protection, monitoring, and restoration |

| Karnataka Fisheries Department | Controlling fishing rights in lakes |

| Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) | Controlling water supply and safe disposal of sewage via sewer lines |

| Karnataka Forest Department | Custodianship, maintenance |

| Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) | Custodianship, planning, and rejuvenation |

| Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority (KTCDA) (formerly the Karnataka Lake Conservation and Development Authority) | Custodianship, planning, rejuvenation, monitoring, policing, evicting encroachments, technical support |

| Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) | Custodianship, restoration, maintenance, monitoring, management of stormwater drains |

| Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) | Environmental regulation by preventing and controlling water pollution |

| Minor Irrigation Department (MID) | Management, protection, conservation and rejuvenation |

A case in point is the original dataset put out by the erstwhile Karnataka Lake Conservation And Development Authority (KLCDA). It does not list all the existing water bodies within the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and BBMP limits. The KLCDA list contains names and locations of only around 210 lakes within the BBMP boundary. Researchers from ATREE found a number of issues in this list: Many lakes' locations were marked wrongly, many were missing, while some in the list had been encroached upon or had dried up.

In 2018, the Karnataka government transferred all responsibilities of the KLCDA to the Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority, which falls under the Minor Irrigation Department.

Currently, the most followed and accessible database for the public and for government agencies is the BBMP's list of lakes, found in CSEI's analysis and interaction with citizen groups. But this is also incomplete and only covers the area under the civic body's jurisdiction. It lists 167 lakes.

Crowdsourcing lake data

Because most of the government datasets are incomplete, incorrect or outdated, there is a need to verify lakes with historical and present images for each lake.

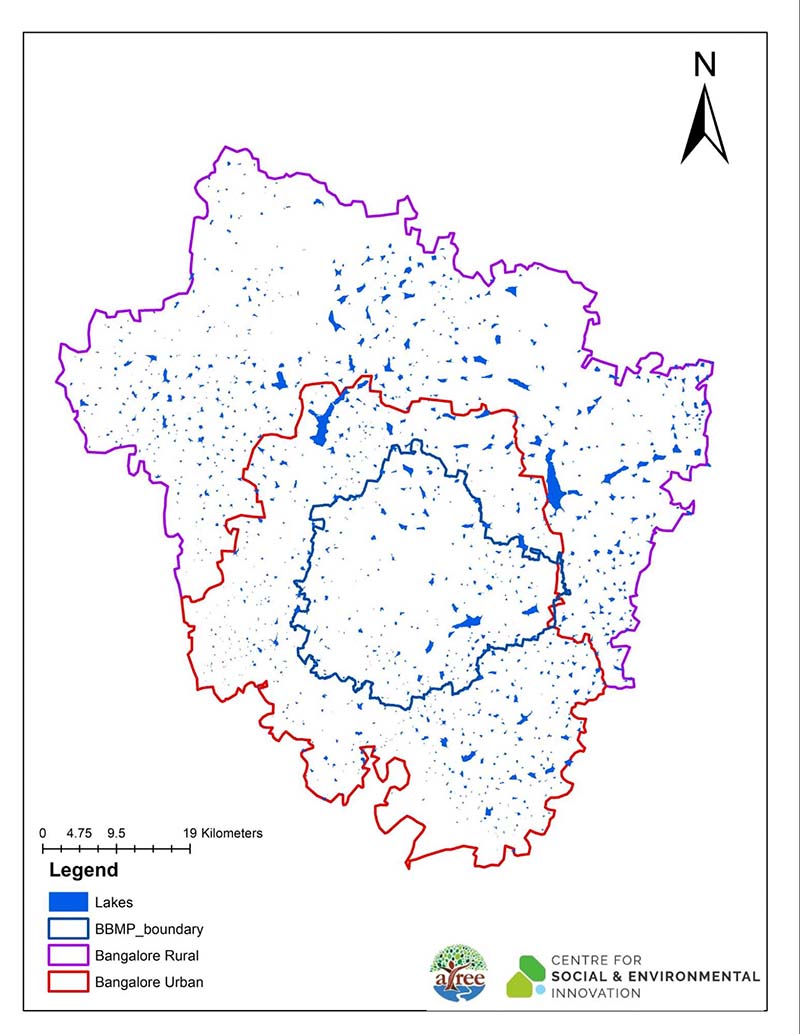

With the help of citizen volunteers, CSEI at ATREE collated lake data from different sources to identify 1,350 lakes spread across Bengaluru--777 lakes in Bengaluru Urban and 573 in Bengaluru Rural. The Urban Lakes Initiative at CSEI, under which this exercise was conducted, works with communities and organisations to collect and curate data, and thus help protect and restore lakes.

CSEI identified water bodies using geo-referenced toposheets (maps that represent three-dimensional land surfaces) sourced from the Survey of India, and Google Earth aerial imagery. CSEI held six training sessions with 35 participants, who learnt to map and verify the location of existing lakes in the city using toposheets and available government data.

These lakes were then manually digitised after verifying their existence by comparing the toposheets and Google Earth imagery. The final dataset contains the location and boundary of both perennial and seasonal lakes in urban and rural districts. The database has details of the lakes' location, boundary, area, custodian details, ward details and citizen lake groups involved in their management.

Bangalore Lakes Masterlist, created by Shashank Palur and Rashmi Kulranjan, Centre for Social and Environmental Innovation, Bengaluru |

The identified lakes are named as per the names on the toposheet or according to the settlement nearest to the lake. This will be updated with access to more government records as will the dataset as more details become available. (If you have more recent information on these lakes, use this form to contribute to this open source project.)

|

Why it is important to fill the lake data gap

The crowdmapping has been turned into a shareable map, which can be used by both government agencies as well as citizen lake groups as a reference. This can enable different stakeholders to make informed decisions about the management of lakes and how to proactively safeguard them.

Currently, clarity on the number of lakes in Bengaluru Rural and Bengaluru Urban districts are missing from government records, said Kaustubh Rau, a biologist documenting Bengaluru's lakes, and a researcher at Azim Premji University (APU), and Ayushi Biswas, a research associate at APU. "Detailed studies on lakes around Bangalore have been not possible due to unavailability of digitised and georeferenced lake data."

Crowdsourcing this work not only sped up the process of discovering and mapping lakes but also made citizens an active part of data gathering and helped them appreciate the complexity of establishing a comprehensive database of lakes that can enable conservation, CSEI found.

This exercise also showed the grim reality of how many lakes had been lost over time due to poor management and underlined the urgency to identify existing lakes before they too are built over. Compared to the 2011 toposheet, which marks 1,558 lakes, about 208 lakes appear to have vanished over a decade, CSEI, which mapped 1,350 lakes, found.

|

|

Open access data of this sort will allow the flow of information between government bodies and the public more easily and crowdsourced maps could be a great starting point for monitoring, supervising, and planning restoration projects by both citizens and governing agencies.

It will help more citizens come forward and collaborate with the government, said Shobha Ananda Reddy, a designate at the Indian Administrative Fellowship under the Karnataka government's panchayat department, and an environmental scientist, who reviewed the dataset. She is also the managing trustee of Jalmitra, a citizens' group working for the revival and maintenance of Rachenahalli lake.

"Usually stakeholders will have information pertaining only to their area of work. For example, the BWSSB focuses on underground drainage; the BBMP's stormwater division has only information related to stormwater flows, etc," Reddy said. "I am optimistic that the database will also enable and simplify the coordination among various stakeholders."

The database can also help identify seasonal lakes, dry lakes, or dry wetland areas, which is necessary considering a lot of lakes in Bengaluru are seasonal and dry up completely during the summer, and might not be identifiable as lakes, added Rau and Biswas of APU.

One of the big problems hampering integrated urban water management is that different stakeholders are not working off the same base data for a wide range of activities, experts said. For example, urban planners need to know where to build sewage treatment plants, where flooding is likely to happen, and conduct land suitability analysis before planning to expand existing cities. Students want to do research; citizen groups want to save their local lakes.

Data is collected and managed in silos, and is largely inaccessible to the public is not a problem unique to Bengaluru, which is why it is necessary to explore the potential of replicating this exercise in other cities.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at satyaagrahindia@gmail.com and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Savitri Devi broke into tears when Yogi Adityanath decided to leave for Gorakhpur to take vow of sainthood, and today her eyes contain the same tears brimming with pride Yogi has emerged as a Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh

- “You need mountains, long staircases don’t make good hikers”: Kalavantin Durg - one of the steepest fortresses in Maharashtra 2,300 feet high trek up this fort is called ‘Climb to Heaven’ because it involves rugged terrain & climbing narrow rock-cut steps

- भारतीय टीमको को करने चाहिए टीम ये तीन बदलाव

- The Balliol college at the University of Oxford has dedicated a new building after Dr. Lakshman Sarup, the first candidate at Oxford to pass his thesis for a Doctorate of Philosophy (DPhil) degree on Sanskrit treatise on etymology

- Liberal Hindu and YouTuber Abhisar Sharma suffers another meltdown within 48 hours, laments media focus on PM Modi while focusing on PM Modi

- How Nehru's Govt helped China in conquering Tibet and let go of it's centuries old friend

- Victims of hate crime Rupesh Pandey, Lavanya, and Kishan gets forgotten while hijab wearing Sharia loyalists get echoed in Supreme Court: A tale of two Indias

- How millennia-old diverse, polytheistic, ‘pagan’ Greco-Roman civilisation gave birth to an intolerant Christian-majority one: a lesson for Hindus

- The real truth about halal which no one wants you to know: Unmasking the Reality of Halal Business Network

- Darul Uloom answers modern questions: Mobile recharging and talking on phone is halal, but taking photos and Job in Paytm is haram and Angels need Identity cards to enter a house

- "One leak will sink a ship: and one sin will destroy a sinner": Hindus protest to stop demolition of old Shani-Hanuman temple, Kejriwal sent team to demolish a temple issuing orders by PWD Delhi in Mandawali after the complaint by Javed, Mansoor, Naushad

- Secularism ideology of India views and appeases Indian Muslims As Pakistanis

- Maulana Tariq Jameel from Deobandi school of Islam claims, "When 130-feet tall Hoor in Jannat points a finger, sun disappears": One Maulana preached that women should offer herself to husband under all circumstances

- ‘The Economist’ slammed by African netizens for romanticising colonial-era bureaucrats that resulted in killing of approx 10 million Congolese

- State-of-the-art Maharaja Bir Bikram Airport Terminal is inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Agartala: Follow Details to know more