More Coverage

Twitter Coverage

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

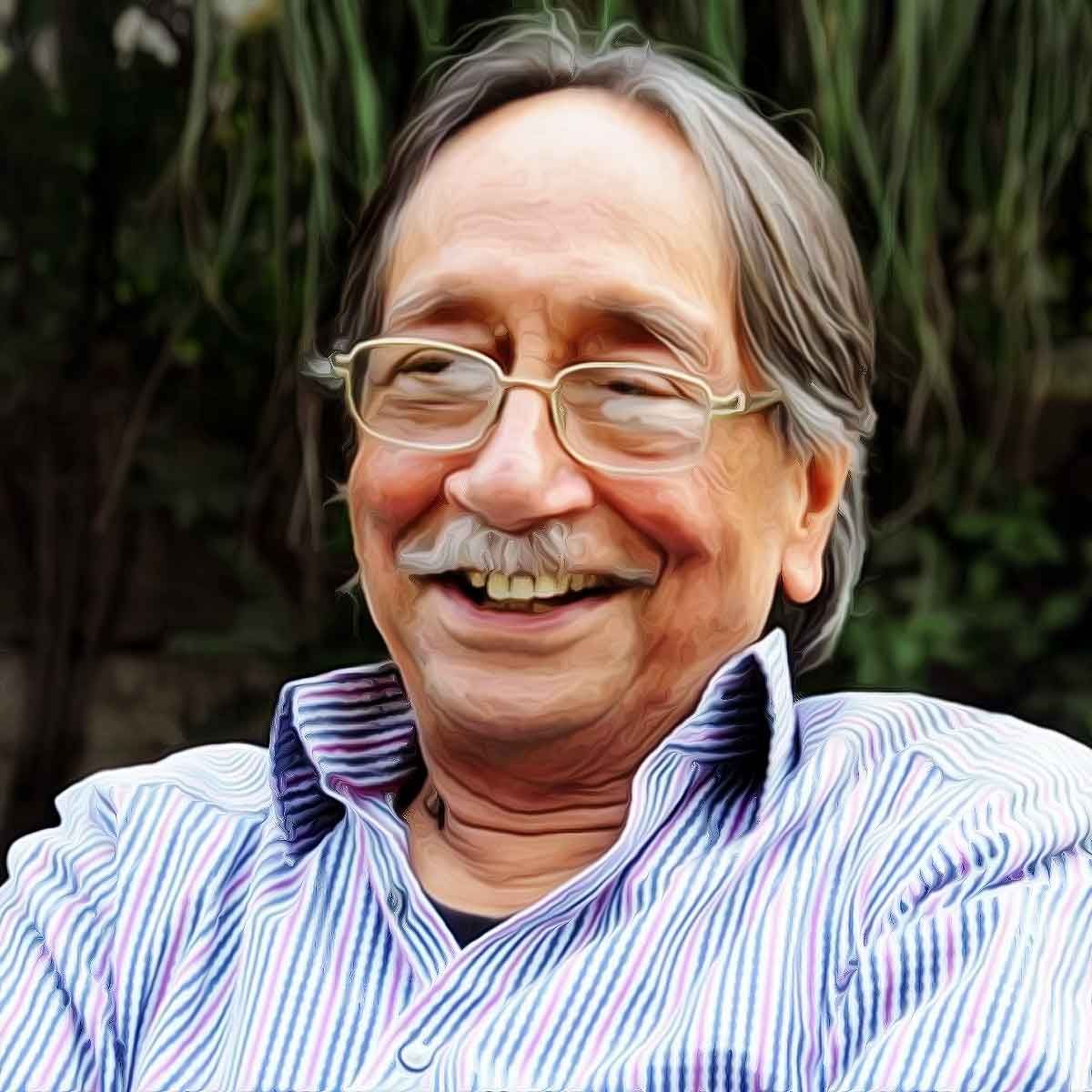

“When a sinister person means to be your enemy, they always start by trying to become your friend”: AS Dulat, who coauthored a book with former ISI chief and described death penalty to Afzal Guru was "unfortunate" joined Rahul Gandhi in Bharat Jodo Yatra

For those unversed with his exploits, it needs to be reiterated that despite his popularity across board, this spymaster has delivered pretty little on the ground.

|

Unlike, say, Ajit Doval, about whom he talks in detail in the chapter, ‘Spooks as Friends’, and who has had remarkable achievements in theatres as diverse and challenging as Mizoram in the Northeast and Pakistan in the west, Dulat’s reputation has been more like a pack of cards just needing a wind of reality check to bring it down.

No doubt, Dulat has good links in Kashmir. So much so that his famed Valley connections gave him the moniker of “Mr Kashmir”. (Brajesh Mishra, Vajpayee’s NSA, would often introduce Dulat as “Yeh sab jaanta hain Kashmir mein.”) But scratch the surface, and it becomes apparent that such connections only helped Dulat and his Valley-based friends, and not India and its national interests.

While Dulat helped legitimise Kashmiri politicians and separatists, the latter on their part made themselves exclusively accessible to the spymaster. This arrangement worked well for Dulat, as he never went into the cold despite achieving very little for the country.

The Government of India before 2014 was obsessed with talking with Kashmiri separatists. For decades it would hold the charade of talks with them, and the end result would be a foregone conclusion: While India would be stuck with these Valley-based leaders, paying them liberally from Indian taxpayers’ money, as Dulat himself concedes in A Life in the Shadows (HarperCollins, Rs 699), the latter made a cottage industry out of the talks with the Centre. It was a win-win scenario for Dulat and these Valley-based leaders — and the only losers in this game of one-upmanship were the people of Kashmir and the Government of India.

|

Dulat’s failures become all the more glaring given the fact that he was witness to some of the most momentous developments in post-Independence India. For, under his watch in the Intelligence Bureau (IB), Kashmir saw a dangerous rise in militancy, especially after the kidnapping of Rubaiya Sayeed in 1989, followed by the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley. Dulat served in Kashmir as Joint Director in the IB from 1988 to 1990, which was arguably the most terror-prone phase in Kashmir.

The IB was so out of touch with ground realities that Dulat himself mentions an incident in the book. “When I first heard of the JKLF boys, I met with one of our better informed deputy SPs on deputation from the Jammu & Kashmir Police, a man called Sapru, and I asked, ‘Sapru sahib, yeh kya ho raha hai? (Sapru sahib, what’s happening?)’ Even he was clueless. He said, ‘Sir, yeh kuch nahin hai. Yeh sab aana jaana chalta rehta hain Kashmir mein. Aap mat ghabrayein (This is nothing really. All this going and coming is routine in Kashmir. Nothing for you to worry about)’.”

If Dulat was out of his depth on the militancy issue, his approach vis-à-vis the killings and exodus of Pandits borders on being insensitive: He clubs the killings of Pandits with IB officials in Kashmir. The fact is, as Jagmohan recounted in his book, My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir, Hindu minorities in the Valley faced assaults and killings that had the sanction of Kashmiri society at large. Police refused to register genocidal crimes, bureaucracy was often seen siding with separatists, and the press took up the cause of terrorists with a passion of a neo-convert.

His stint with the R&AW was equally disastrous, as India failed to foresee the 1999 Kargil conflict; this was followed by the hijacking of the Indian Airlines Flight 814 to Kandahar in December that very year, resulting in the meek surrender of three dreaded terrorists including Azhar Masood. Two years later, the Indian Parliament was the epicenter of a terror attack.

Maybe someone in the Vajpayee dispensation thought being ‘Mr Kashmir’ was a good enough qualification for being the R&AW chief. In A Life in the Shadows, Dulat concedes, though inadvertently, how R&AW wasn’t his home ground. He writes, “At a time when my mind was blank about how to deal with the posting at the R&AW, Kashmir would save me in many ways, allowing me to give nuanced perspectives on otherwise straightforward perspectives.”

|

Dulat’s “Aman Ki Asha” mindset wouldn’t let him see beyond Lahore, where Vajpayee had arrived with much fanfare to mend ties with Pakistan in 1999. Little did he realise that his peace overtures would land his troops in Kargil in less than six months.

There’s no doubt that Dulat was excellent in interpersonal skills. He created personal connections with Kashmir’s political and separatist elements. But he lacked the Doval-like rigour and discipline to mix the talks with tough measures. Any good spymaster would require judicious mix of soft and hard intelligence.

When Dulat was first posted in Srinagar in May 1988, his mandate was simple: To Keep Farooq Abdullah on the right side. Unfortunately, as we look at his relations with Farooq, it is obvious that instead of keeping Farooq on the right side, Dulat has worked hard to keep himself on the right side of Farooq. His loyalty towards Farooq has been absolute.

Dulat calls him Kashmir’s tallest leader and “an asset” for New Delhi. However, as we look at Farooq’s track record, he appears to be a liability — a wily customer who shifts his stance and goalposts to suit his interests. Even in Dulat’s own book, Farooq comes across as a politician who often has the cake and eats it too. “Farooq… suffers from no illusions that Kashmir can ever be permanently solved,” Dulat quotes a top Shia leader in the Valley as saying, quite approvingly.

It’s obvious that there’s no easy way out for Kashmir. But what Dulat and his ilk, deliberately or otherwise, fail to understand is that the likes of Farooq Abdullah and Mirwaiz Umar Farooq are part of the Kashmiri problem, and not the solution. They have vested interests in keeping the Kashmir fire burning.

For, the besieged Valley helped them lead an affluent life on Indian taxpayers’ money, protected by Indian agencies; still they have no qualms in opportunistically wearing the Gandhian cloak to project themselves as freedom fighters. Dulat needs to explain why India should continue to tread the same, old beaten path despite no substantial gains in the past 70 years. If a policy doesn’t bear fruits for that long, then it’s common sense to change it.

|

Dulat has been a votary of ‘Kashmiriyat’, an imagined state of Kashmiri-ness often invoked to hide the brutal, violent face of Kashmir, especially since the late 1980s. While he concedes that Kashmiriyat won’t survive in the Valley without the Pandits, he in the same breath says that 2016 was “the beginning of the end of Kashmir as we knew it”.

No, Mr Dulat, Kashmir didn’t change in 2016, it has been changing for the past 600 years, and the last big cataclysmic change took place in 1990 when the Pandits were forced to leave Kashmir, fearing for their lives after some of them were selectively killed, while the majority Muslim community either supported the killings silently or chose to look the other way round. Their discrimination and selective anguish continue to this day.

Dulat says, “We spooks are sinners, after all — more than saints. We talk to our enemies more than we talk to our friends.” As a spymaster, he was expected to talk to his enemies. However, over the decades, and as his latest book suggests, he seemed to have blurred the fine line between enemies and friends. It’s this ambivalence — or, worse, sympathies for his adversaries — that has been his worst failing. One hopes India has seen the last of the Dulat-ian experiments in Kashmir — and with Pakistan.

References:

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at satyaagrahindia@gmail.com and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- Knowing no boundary for hate, liberals descended on social media platforms to celebrate the death of legendary singer Lata Mangeshkar, calling her a ‘fascist’ and a ‘vile sanghi’

- Wikipedia dismisses Love Jihad as a conspiracy theory by Hindus, but claims reverse Love Jihad against Muslims is real

- "Today I realise how lucky we are as Indians”, from staunch critic to newfound admirer, Shehla Rashid's 'epiphany' lauds PM Modi's peace efforts in Kashmir. Perhaps, it's the aftertaste of recent prosecution sanctions that's led to this change of heart

- Why India’s temples must be freed from government control

- Explore the intense reactions to Ayodhya's Ram Mandir Pran Pratishtha, from Pakistan's critical stance and Indian left-liberals' outcry, to archaeologist KK Mohammad's call for Muslims to hand over disputed Gyanvapi, Shahi Idgah Structure to Hindus

- British colonization mindset still prevails: Sardar Udham's entry rejected in Oscars because “It projects hatred towards British"

- Violent mob throwing stones, and radicals chopping off limbs is okay for ‘Liberals’ but a Hindu tweeting dislike for an ad is dangerous

- "Sarfaroshi ki tamanna ab hamare dil me hai, dekhna hai zor kitna baazu-e-Amnesty me hai": ED alleged Amnesty India is ‘kingpin’ of Breaking India forces, routed Rs 51 crore violationing FCRA to “fund anti-national activities in guise of export of service

- "Diving deep into the Congress-China connection reveals a web of ties": Jairam Ramesh's Huawei affinity, the Gandhis' MoU with CCP, and closed-door meetings; such undisclosed affiliations raise questions about transparency and India's sovereignty

- "Andolanjeevi": Case registered against ‘activist’ Medha Patkar, who gained notoriety in a cheating case of “Narmada Bachao Andolan,” accused of misusing funds of educating tribal children, received donation in crores for her NGO

- Lt Col Purohit's shocking testimony to the NIA court exposes torture by ATS to force accusations against RSS, VHP, and Yogi Adityanath in the Malegaon blast, revealing deep-seated plots involving ISI agents and an attempt to coin the term 'Saffron Terror'

- "Manipulating minds, one tweet at a time": China cunningly exploits global social media, manipulating opinions through a web of deceit, Oxford Internet Institute exposesunchecked cyber onslaught, revealing China's ambitions to control global narratives

- Fan pages of former Congress leaders, managed by the Congress IT cell rebranded as Maktoob media: Propaganda portal, publicizing Islamic propaganda and Hindumisia content, promoted by terror apologists

- Here is a list of 20 incidents where the ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogan has been misused to turn a random crime into ‘hate crime’

- IT Dept unearths scam in ‘Believers Eastern Church’, funds for charity used to run Churches, proselytisation, got Rs 7,000 crore over the years: Details