Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

When Nehru ignored warnings from Sardar Patel and Sri Aurobindo and shocked USA President: Chinese Betryal and loss of centuries old ally

On October 31, the world’s tallest statue, the Statue of Unity dedicated to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was unveiled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.The work on the 182-metre tall statue has been completed after round the clock work by 3,400 labourers and 250 engineers at Sadhu Bet island on Narmada river in Gujarat. Sadhu Bet, located some 3.5 km away from the Narmada Dam, is linked by a 250-metre-long long bridge.

Unfortunately, for several reasons, scarce scholarly research has been done on the internal history of the Congress; the main cause is probably that a section of the party would prefer to keep history under wraps. Take the acute differences of opinion between Sardar Patel, the deputy prime minister, and “Panditji”, as Nehru was then called by Congressmen. In the last weeks of Patel’s life (he passed away on December 15, 1950), there was a deep split between the two leaders, leading to unilateral decisions for the PM, for which India had to pay the heaviest price.

The most serious cause of discord was the invasion of Tibet by the Chinese “Liberation Army” in October 1950. In the course of recent researches in Indian archives, I discovered several new facts. Not only did several senior Congress leaders, led by Patel, violently oppose Nehru’s suicidal policy, but many senior bureaucrats too did not agree with the Prime Minister’s decisions and objected to his policy of appeasement with China, which led India to lose a peaceful border.

Invasion of Tibet by the Chinese “Liberation Army" |

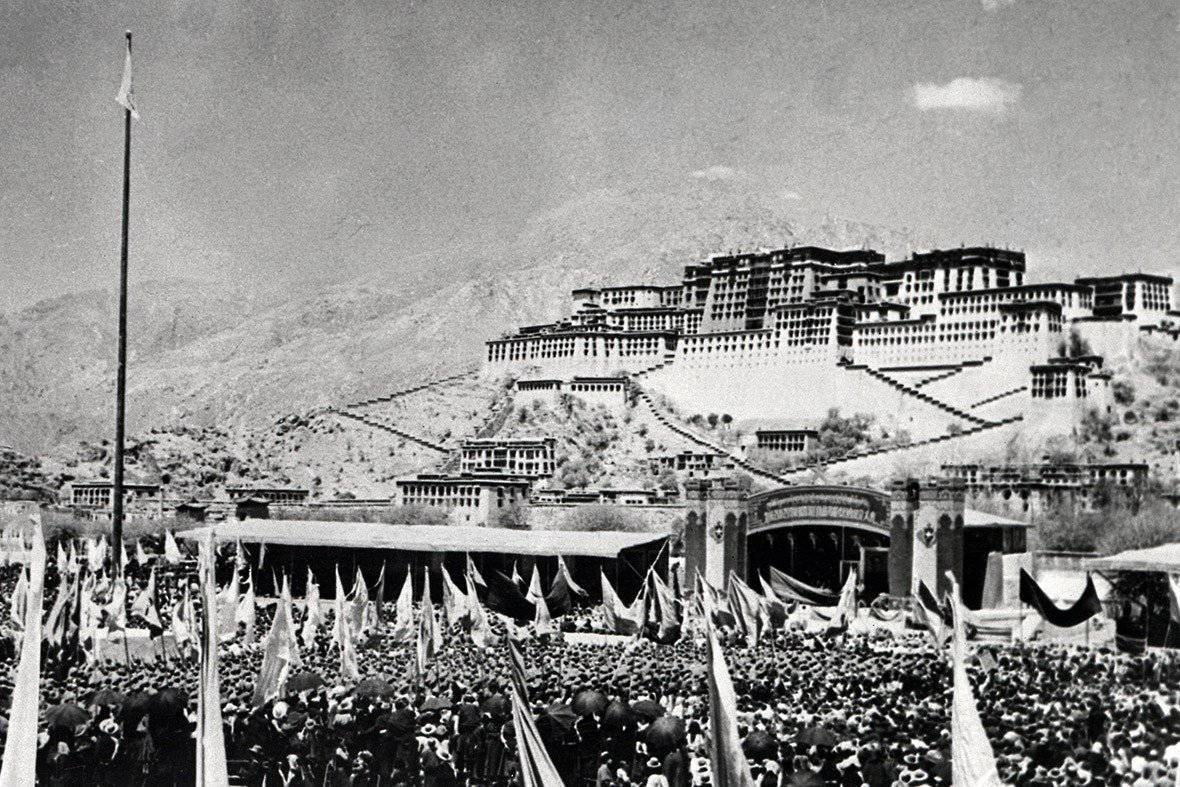

In the year 1950, two momentous events shook Asia and the world. One was the Chinese invasion of Tibet, and the other, the Chinese intervention in the Korean War.

The first was near, on India’s borders, the other, far away in the Korean Peninsula where India had little at stake. By all canons of logic, India should have devoted utmost attention to the immediate situation in Tibet, and let interested parties like China and the U.S. sort it out in Korea.

But Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s Prime Minister did exactly the opposite. He treated the Tibetan crisis in a haphazard fashion, while getting heavily involved in Korea. India today is paying for this folly by being the only country of its size in the world without an official boundary with its giant neighbor.

Tibet soon disappeared from the map. As in Kashmir, Nehru sacrificed national interest at home in pursuit of international glory abroad.

The Crisis Today and National Amnesia

It is often said that ‘those who forget history are condemned to repeat it’. The truth of this adage is seldom realized. With the brutal and savage killings of unarmed Indian soldiers by the death squads of the People’s Liberation Army, (PLA) and the brazen claims of China over the entire Galwan valley of Ladakh and other vital territories that historically belonged to India, we seem to have come full circle from the debacle of 1962 when the nation had been given a deadly body blow by Chinese aggression in the then NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh) and other areas currently under the gaze of Chinese expansionism. Despite the passage in time, history seems to repeat itself. What is the way out? Could some of the earlier missing narratives help in our understanding as a new India is emerging?

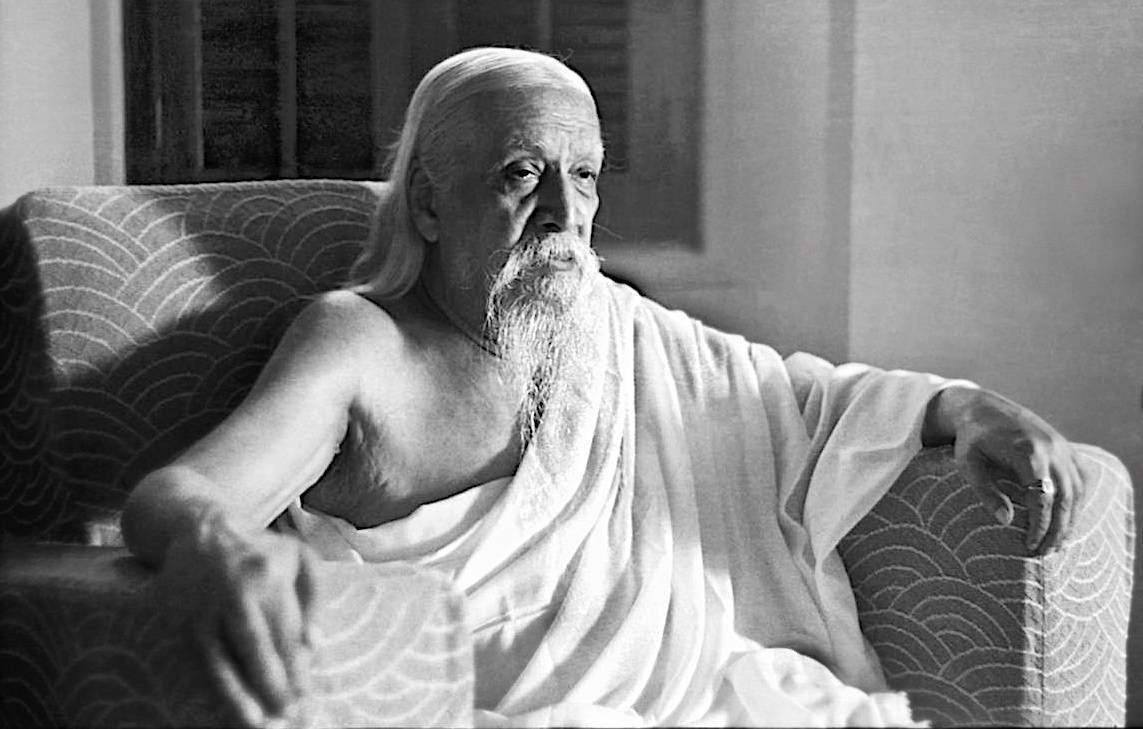

Sri Aurobindo |

Sri Aurobindo's insight

Sri Aurobindo's insight into the 1950 Korean conflict foretold the possibility and consequences of China's invasion on Tibet and aggression against India in 1962, reveals the book "Sri Aurobindo: A Contemporary Reader" written by Prof Sachidananda Mohanty, former Vice-Chancellor of the Central University of Orissa and former Professor and Head, Department of English, University of Hyderabad.

According to the book "Sri Aurobindo: A Contemporary Reader" by Prof Sachidananda Mohanty, on June 28, 1950, Sri Aurobindo wrote a letter to KD Sethna, editor of Mother India, in reply to his question on the conflict in Korea, describing the situation there as "the first move in the Communist plan of campaign to dominate and take possession first of these northern parts and then of South East Asia as a preliminary to their manoeuvres with regard to the rest of the continent — in passing, Tibet as a gate opening to India." Some months later, in the wake of China's invasion of Tibet in October 1950, Sethna wrote an editorial "The Truth About Tibet" which elaborated on the views expressed in Sri Aurobindo's earlier letter to him.

On 28 March 1963, Sudhir Ghosh, the eminent Indian emissary of Gandhiji, and later of Jawaharlal Nehru, met with the President of the United States, John F Kennedy in the White House and shared the last testament of Sri Aurobindo [about the Chinese invasion of Tibet] that had appeared in Mother India on 11 November 1950 before Sri Aurobindo’s passing on 5 December 1950:

"The basic significance of Mao's Tibetan adventure is to advance China's frontiers right down to India and stand poised there to strike at the right moment and with the right strategy — unless India precipitately declares herself on the side of the Russian bloc. But to go over to Mao and Stalin in order to avert their wrath is not in any sense a saving gesture. It is a gesture spelling the utmost ruin to all our ideals and aspirations. Really the gesture that can save is to take a firm line with China, denounce openly her nefarious intentions, stand without reservation by the USA and make every possible arrangement consonant with our own self-respect to facilitate an American intervention in our favour and, what is of still greater moment, an American prevention of Mao's evil designs on India. Militarily, China is almost ten times as strong as we are, but India as the spearhead of an American defence of democracy can easily halt Mao's mechanised millions. And the hour is upon us of constituting ourselves such a spearhead and saving not only our own dear country but also all South East Asia whose bulwark we are. We must burn it into our minds that the primary motive of Mao's attack on Tibet is to threaten India as soon as possible." - Sri Aurobindo - November 11, 1950

Sri Aurobindo’s views on totalitarian Communism was an established fact reflected in his letters and socio-political writings. Freedom, he declared, was indispensable for human progress.

What then is the way out in the crisis in Tibet? The editorial continued:

The gesture that can save is to take a firm line with China, denounce openly her nefarious intentions, stand without reservations by the USA and make every possible arrangement consonant with our self-respect to facilitate an American intervention in our favour, and, what is still of greater moment, an American prevention of Mao’s evil design in India. Militarily, China is almost ten times as strong as we are, but India as the spearhead of an American defence of democracy can easily halt Mao’s mechanized millions.

[Sudhir Ghosh, Gandhi’s Emissary, New Delhi: Routledge,2008, pp.277-78. First published in the USA, by Houghton Mifflin Company, 1967. Also see, Sri Aurobindo: A Contemporary Reader by Sachidananda Mohanty, Routledge,2008; rpt.2016, pp.221-222 ]

Sudhir Ghosh, a distinguished member of Parliament of the hallowed years and close confidant of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in forging strategic ties with the USA immediately after Chinese attack on India in 1962 |

As Ghosh records: “The President read the words of Sri Aurobindo’s last testament several times over and said:

“Surely there must be some typing mistake here. The date must have been 1960 and not 1950. You mean to say that a man devoted to meditation and contemplation, sitting in one corner of India, said this about the intentions of Communist China as early as 1950?"

He was somewhat shocked. ‘So, there you are,’ said the President. ‘One great Indian, Nehru, showed you the path of non-alignment between China and America, and another great Indian Aurobindo, showed you another way of survival. The choice is up to the people of India.'

Earlier in the meeting, Ghosh had shared with the President, Nehru’s letter, and this is how Ghosh records the reaction of Kennedy who was frankly quite indignant:

The President read it slowly and carefully and ruefully remarked: ‘He [Nehru] cannot sacrifice non-alignment, eh? Are the people of India non-aligned between Communist China and the United States? I don’t believe that anybody in India is non-aligned between China and the United States—except of course the Communists and their fellow travellers.’ Then some thing fell from his lips which was perhaps unintentional. He indignantly said that only a few months earlier when Mr Nehru was overwhelmed by the power of Communist China he made desperate appeal to him for air protection, and non-alignment or no non-alignment, the President had to respond. He added sarcastically that Mr Nehru’s conversion lasted only a few days. He was impressed to see the speed with which the Prime Minister swung back to his original position with regard to the United States. [ Gandhi’s Emissary, p.276.]

Today as we keep wrestling with the question of the Chinese intrusions into the Indian territory, more than five decades down the line, and their growing demands and claims for our lands, it is worth recalling the two forgotten chapters from Indian history in 1950.

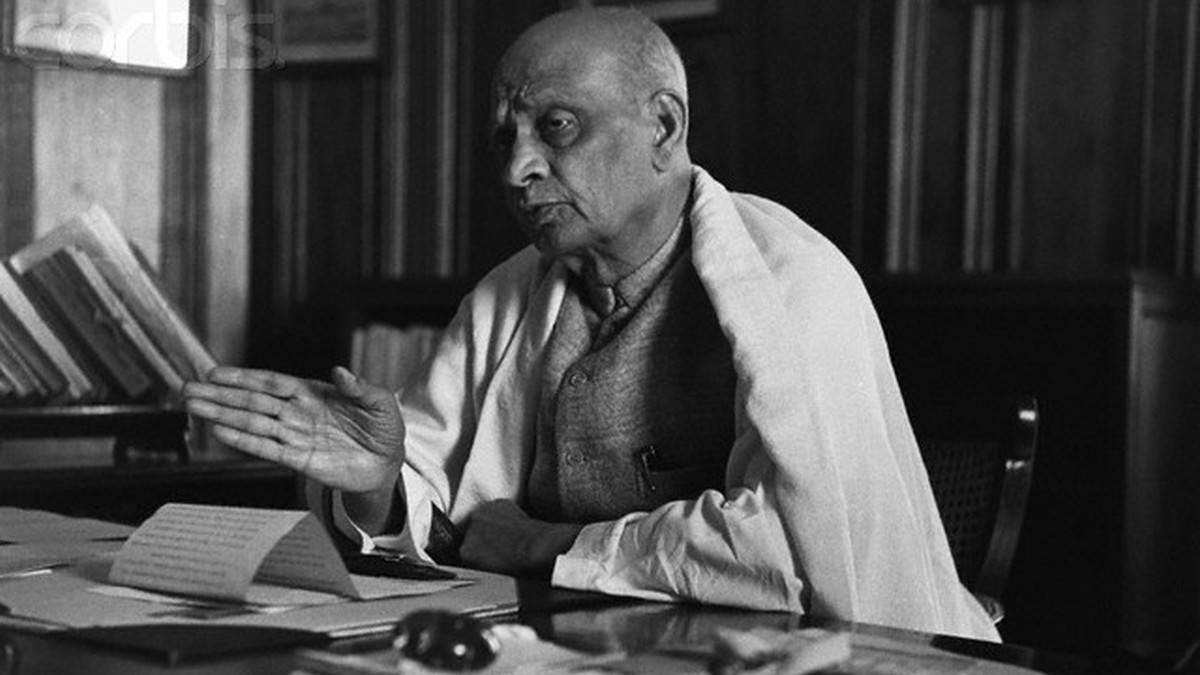

Just as Sri Aurobindo, in his last letter to the Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, dated 7 Nov.1950, Sardar Patel, the then Home Minister wrote, “The Chinese government has tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intention… They managed to instil into our Ambassador a false sense of confidence in their so called desire to settle the Tibetan problem by peaceful means... The action of the Chinese, in my judgment, is little short of perfidy.”

Patel’s letter described in detail the situation along the northern border of India and warned against the possibility of invasion and advised the Government of India to take action. In his letter, Patel also pointed out about the reality of the India-China relationship,“… even though we regard ourselves as friends of China, the Chinese do not regard us as their friends. With the Communist mentality of 'whoever is not with them being against them', this is a significant pointer, of which we have take due note,” wrote Patel.

“During the last several months, outside the Russian camp, we have practically been alone in championing the cause of Chinese entry into the UNO, and in securing from the Americans assurances on the question of Formosa. We have done everything we could to assuage Chinese feelings, to allay its apprehension and to defend its legitimate claims, in our discussions and correspondence with America and Britain and in the UNO. In spite of this, China is not convinced about our disinterestedness, it continues to regard us with suspicion and the whole psychology is one, at least outwardly of scepticism, perhaps mixed with a little hostility, I doubt if we can go any further than we have done already to convince China of our good intentions, friendliness and goodwill," he added.

Patel passed away a little over a month after writing this letter.

|

Here's the complete text of that letter

My dear Jawaharlal, ever since my return from Ahmedabad and after the Cabinet meeting the same day which I had to attend at practically 15 minutes’ notice and for which I regret I was not able to read all the papers, I have been anxiously thinking over the problem of Tibet and I thought I should share with you what is passing through my mind.

I have carefully gone through the correspondence between the External Affairs Ministry and our Ambassador in Peking and through him the Chinese Government. I have tried to peruse this correspondence as favourably to our Ambassador and the Chinese Government as possible, but I regret to say that neither of them comes out well as a result of this study.

‘Chinese Do Not Regard Us As Friends’

The Chinese Government has tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intentions. My own feeling is that at a crucial period they managed to instil into our Ambassador a false sense of confidence in their so-called desire to settle the Tibetan problem by peaceful means. There can be no doubt that during the period covered by this correspondence, the Chinese must have been concentrating for an onslaught on Tibet.

The final action of the Chinese, in my judgement, is little short of perfidy. The tragedy of it is that the Tibetans put faith in us; they chose to be guided by us; and we have been unable to get them out of the meshes of Chinese diplomacy or Chinese malevolence.

From the latest position, it appears that we shall not be able to rescue the Dalai Lama. Our Ambassador has been at great pains to find an explanation or justification for Chinese policy and actions.

Therefore, if the Chinese put faith in this, they must have distrusted us so completely as to have taken us as tools or stooges of Anglo-American diplomacy or strategy. This feeling, if genuinely entertained by the Chinese in spite of your direct approaches to them, indicates that even though we regard ourselves as friends of China, the Chinese do not regard us as their friends.

With the Communist mentality of “whoever is not with them being against them”, this is a significant pointer, of which we have to take due note.

We have done everything we could to assuage Chinese feelings, to allay its apprehensions and to defend its legitimate claims in our discussions and correspondence with America and Britain and in the UNO.

In spite of this, China is not convinced about our disinterestedness; it continues to regard us with suspicion and the whole psychology is one, at least outwardly, of scepticism, perhaps mixed with a little hostility. I doubt if we can go any further than we have done already to convince China of our good intentions, friendliness and goodwill.

In Peking we have an Ambassador who is eminently suitable for putting across the friendly point of view. Even he seems to have failed to convert the Chinese. Their last telegram to us is an act of gross discourtesy not only in the summary way it disposes of our protest against the entry of Chinese forces into Tibet, but also in the wild insinuation that our attitude is determined by foreign influences. It looks as though it is not a friend speaking in that language but a potential enemy.

‘Communism Is No Shield Against Imperialism’

In the background of this, we have to consider what new situation now faces us as a result of the disappearance of Tibet, as we knew it, and the expansion of China almost up to our gates.

Throughout history we have seldom been worried about our north-east frontier. The Himalayas have been regarded as an impenetrable barrier against any threat from the north.

We had a friendly Tibet which gave us no trouble. The Chinese were divided. They had their own domestic problems and never bothered us about our frontiers. In 1914, we entered into a convention with Tibet which was not endorsed by the Chinese.

We seem to have regarded Tibetan autonomy as extending independent treaty relationship.

Presumably, all that we required was Chinese counter-signature. The Chinese interpretation of suzerainty seems to be different. We can, therefore, safely assume that very soon they will disown all the stipulations which Tibet has entered into with us in the past.

All along the Himalayas in the north and north-east, we have on our side of the frontier a population ethnologically and culturally not different from Tibetans or Mongoloids.

The undefined state of the frontier and the existence on our side of a population with its affinities to Tibetans or Chinese have all the elements of potential trouble between China and ourselves.

Recent and bitter history also tells us that communism is no shield against imperialism and that the Communists are as good or as bad imperialists as any other. Chinese ambitions in this respect not only cover the Himalayan slopes on our side but also include important parts of Assam.

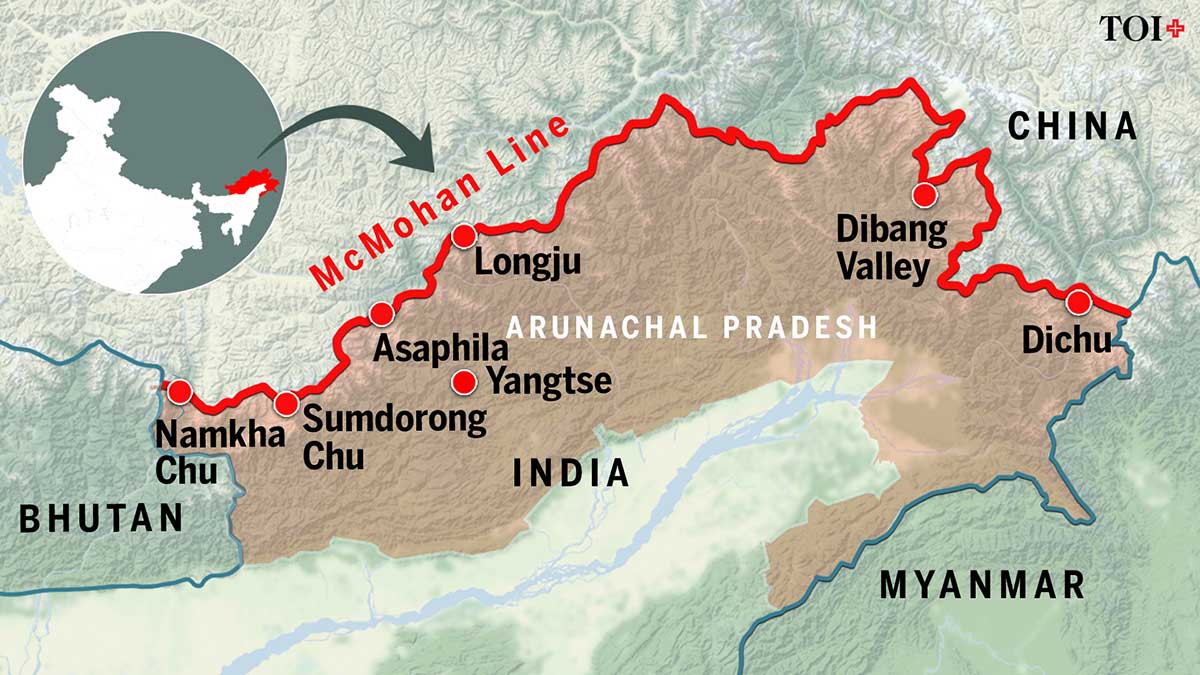

They have their ambitions in Burma also. Burma has the added difficulty that it has no McMahon Line round which to build up even the semblance of an agreement. Chinese irredentism and Communist imperialism are different from the expansionism and imperialism of the Western Powers.

While our western and north-western threat to 8 security is still as prominent as before, a new threat has developed from the north and north-east. Thus, for the first time after centuries, India’s defence has to concentrate itself on two fronts simultaneously.

Our defence measure have so far been based on the calculations of a superiority over Pakistan. In our calculations we shall now have to reckon with Communist China in the north and in the north-east, a Communist China which has definite ambitions and aims and which does not, in any way, seem friendly disposed towards us.

‘Unlimited Scope For Infiltration’

Let us also consider the political conditions on this potentially troublesome frontier. Our northern or north-eastern approaches consist of Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, the Darjeeling [area] and tribal areas in Assam.

From the point of view of communications, they are weak spots. Continuous defensive lines do not exist. There is almost an unlimited scope for infiltration. Police protection is limited to a very small number of passes. There, too, our outposts do not seem to be fully manned.

The contact of these areas with us is by no means close and intimate. The people inhabiting these portions have no established loyalty or devotion to India. Even the Darjeeling and Kalimpong areas are not free from pro-mongoloid prejudices.

During the last three years, we have not been able to make any appreciable approaches to the Nagas and other hill tribes in Assam. European missionaries and other visitors had been in touch with them, but their influence was in no way friendly to India or Indians. In Sikkim there was political ferment some time ago.

In these circumstances, to make people alive to the new danger or to make them defensively strong is a very difficult task indeed and that difficulty can be got over only by enlightened firmness, strength and a clear line of policy.

I am sure the Chinese and their source of inspiration, Soviet Russia, would not miss any opportunity of exploiting these weak spots, partly in support of their ideology and partly in support of their ambitions. In my judgement, the situation is one in which we cannot afford either to be complacent or to be vacillating.

We must have a clear idea of what we wish to achieve and also of the methods by which we should achieve it. Any faltering or lack of decisiveness in formulating our objectives or in pursuing our policy to attain those objectives is bound to weaken us and increase the threats which are so evident.

‘Communist Threats To Our Security’

Side by side with these dangers, we shall now have to face serious internal problems as well. I have already asked [H.V.R.] Ienger to send to the E. A. Ministry a copy of the Intelligence Bureau’s appreciation of these matters.

Hitherto, the Communist Party of India has found some difficulty in contacting Communists abroad, or in getting supplies of arms, literature, etc. from them. They had to content with the difficult Burmese and Pakistan frontiers on the east or with the long seaboard.

They shall now have a comparatively easy means of access to Chinese Communists and through them to other foreign Communists. Infiltration of spies, fifth columnists and Communists would now be easier.

The whole situation thus raises a number of problems on which we must come to an early decision so that we can, as I said earlier, formulate the objectives of our policy and decide the methods by which those objectives are to be attained.

It is also clear that the action will have to be fairly comprehensive, involving not only our defence strategy and state of preparations but also problems of internal security to deal with which we have not a moment to lose.

We shall also have to deal with administrative and political problems in the weak spots along the frontier to which I have already referred.

‘Problems That Need To Be Addressed’

It is, of course, impossible for me to be exhaustive in setting out all these problems. I am, however, giving below some of the problems which, in my opinion, require early solution and around which we have to build our administrative or military 10 policies and measures to implement them.

- A military and intelligence appreciation of the Chinese threat to India both on the frontier and to internal security.

- An examination of our military position and such redisposition of our forces as might be necessary, particularly with the idea of guarding important routes or areas which are likely to be the subject of dispute.

- An appraisement of the strength of our forces and, if necessary, reconsideration of our retrenchment plans for the Army in the light of these threats.

- A long-term consideration of our defence needs. My own feeling is that, unless we assure our supplies of arms, ammunition and armour, we should be making our defence position perpetually weak and we would not be able to stand up to the double threat of difficulties both from the west and north-west and north and north-east.

- The question of Chinese entry into UNO. In view of the rebuff which China has given us and the method which it has followed in dealing with Tibet, I am doubtful whether we can advocate its claim any longer. There would probably be a threat in the UNO virtually to outlaw China in view of its active participation in the Korean war. We must determine our attitude on this question also.

- The political and administrative steps which we should take to strengthen our northern and north-eastern frontiers. This would include the whole of the border, i.e. Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling and the tribal territory in Assam.

- Measures of internal security in the border areas as well as the States flanking those areas, such as U.P., Bihar, Bengal and Assam.

- Improvement of our communications, road, rail, air and wireless, in these areas and with the frontier outposts.

- The future of our mission at Lhasa and the trade posts at Gyangtse and Yatung and the forces which we have in operation in Tibet to guard the trade routes. (j) The policy in regard to the McMahon Line.

These are some of the questions which occur to my mind. It is possible that a consideration of these matters may lead us into wider questions of our relationship with China, Russia, America, Britain and Burma.

This, however, would be of a general nature, though some might be basically very important, e.g. we might have to consider whether we should not enter into closer association with Burma in order to strengthen the later in its dealings with China. I do not rule out the possibility that, before applying pressure on us, China might apply pressure on Burma.

suggest that we meet early to have a general discussion on these problems and decide on such steps as we might think to be immediately necessary and direct quick examination of other problems with a view to taking early measures to deal with them.

Yours,

Sd/- Vallabhbhai Patel

The Hon’ble Shri Jawaharlal Nehru New Delhi.

On November 9, 1950, two days after he wrote the letter to Nehru, he announced in Delhi: ‘In Kali Yuga, we shall return ahimsa for ahimsa. If anybody resorts to force against us, we shall meet it with force.’ But Nehru ignored Patel’s letter. The truth is that India was in a strong position to defend its interests in Tibet, but gave up the opportunity for the sake of pleasing China. It is not widely known in India that in 1950, China could have been prevented from taking over Tibet.

Patel on the other hand recognized that in 1950, China was in a vulnerable position, fully committed in Korea and by no means secure in its hold over the mainland. For months General MacArthur had been urging President Truman to “unleash Chiang Kai Shek” lying in wait in Formosa (Taiwan) with full American support. China had not yet acquired the atom bomb, which was more than ten years in the future. India had little to lose and everything to gain by a determined show of force when China was struggling to consolidate its hold.

In addition, India had international support, with world opinion strongly against Chinese aggression in Tibet. The world in fact was looking to India to take the lead. The highly influential English journal The Economist echoed the Western viewpoint when it wrote: ‘Having maintained complete independence of China since 1912, Tibet has a strong claim to be regarded as an independent state. But it is for India to take a lead in this matter. If India decides to support independence of Tibet as a buffer state between itself and China, Britain and U.S.A. will do well to extend formal diplomatic recognition to it.’

So China could have been stopped. But this was not to be. Nehru ignored Patel’s letter as well as international opinion and gave up this golden opportunity to turn Tibet into a friendly buffer state. With such a principled stand, India would also have acquired the status of a great power while Pakistan would have disappeared from the radar screen of world attention.

Much has been made of Nehru’s blunder in Kashmir, but it pales in comparison with his folly in Tibet. As a result of this monumental failure of vision—and nerve—India soon came to be treated as a third rate power, acquiring ‘parity’ with Pakistan. Two months later Patel was dead.

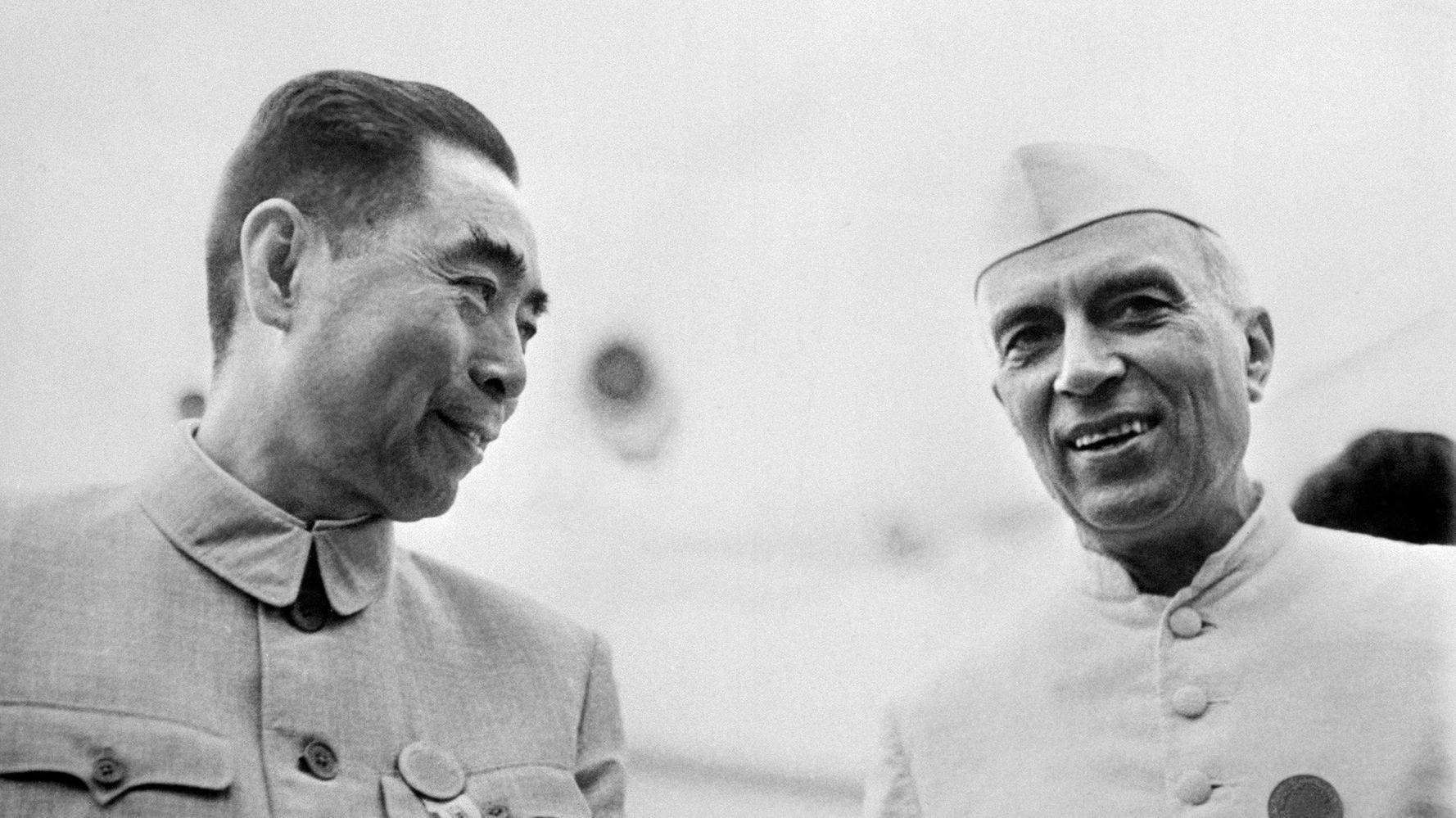

Even after the loss of Tibet, Nehru gave up opportunities to settle the border with China. To understand this, it is necessary to appreciate the fact that what China desired most was a stable border with India. With this in view, the Chinese Premier Zhou-en-Lai visited India several times to fix the boundary between the two countries.

In short, the Chinese proposal amounted to the following: they were prepared to accept the McMahon Line as the boundary in the east—with possibly some minor adjustments and a new name—and then negotiate the unmarked boundary in the west between Ladakh and Tibet. In effect, what Zhou-en-Lai proposed was a phased settlement, beginning with the eastern boundary. Nehru, however, wanted the whole thing settled at once. The practical minded Zhou-en-Lai found this politically impossible.

And on each visit, the Chinese Premier in search of a boundary settlement, heard more about the principles of Pancha Sheela than India’s stand on the boundary. He interpreted this as intransigence on India’s part.

China does not recognise the McMahon Line and believes Arunachal is part of its territory |

Pancha Sheela (Principles of the Panchsheel Agreement)

The Panchsheel Agreement served as the foundation for India-China relations. It would advance economic and security cooperation between the two nations. The implied assumption of the Fiver Principles was that newly independent states after decolonisation would develop a more pragmatic approach towards international relations.

The Five Principles of the Panchsheel Agreement are as follows:

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty,

- Mutual non-aggression

- Mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs,

- Equality and mutual benefit

- Peaceful co-existence

The 5 principles were emphasized by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai in a broadcast speech made at the time of Asian Prime Ministers Conference in Colombo, Sri Lanka after signing the Sino-Indian Agreement in Beijing.

China in fact went on to settle its boundary with Myanmar (Burma) roughly along the McMahon Line following similar principles. Contrary to what the Indian public was told, the border between Ladakh (in the Princely State of Kashmir) and Tibet was never clearly demarcated.

As late as 1960, the Indian Government had to send survey teams to Ladakh to locate the boundary and prepare maps. But the Government kept telling the people that there was a clearly defined boundary, which the Chinese were refusing to accept.

What the situation demanded was a creative approach, especially from the Indian side. There were several practical issues on which negotiations could have been conducted—especially in the 1950s when India was in a strong position.

China needed Aksai Chin because it had plans to construct an access road from Tibet to Xinjiang province (Sinkiang) in the west. Aksai Chin was of far greater strategic significance to China than to India. (It may be a strategic liability for India—being expensive to maintain and hard to supply, even more than the Siachen Glacier.)

Had Nehru recognized this he might have proposed a creative solution like asking for access to Mount Kailash and Manasarovar in return for Chinese access to Aksai Chin. The issue is not whether such an agreement was possible, but no solutions were proposed. The upshot of all this was that China ignored India—including Pancha Sheel—and went ahead with its plan to build the road through Aksai Chin.

This is still not the full story.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES: Picture taken from the 50s of Indian prime minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, in official visit in China, talking with his chinese counterpart Zhou Enlai. Indian statesman and prime minister (1947-64) |

On the heels of this twin blunder—abandonment of Tibet and sponsorship of China with nothing to show in return—Nehru deceived the Indian public in his pursuit of international glory through Pancha Sheel.

Pancha Sheel, which was the principal ‘policy’ of Nehru towards China from the betrayal of Tibet to the expulsion of Dalai Lama in 1959, is generally regarded as a demonstration of good faith by Nehru that was exploited by the Chinese who ‘stabbed him in the back’. This is not quite correct, for Nehru (and Krishna Menon) knew about the Chinese incursions in Ladakh and Aksai Chin but kept it secret for years to keep the illusion of PanchaSheel alive.

General Thimayya had brought the Chinese activities in Aksai Chin to the notice of Nehru and Krishna Menon several years before that. An English mountaineer by name Sydney Wignall was deputed by Thimayya to verify reports that the Chinese were building a road through Aksai Chin. He was captured by the Chinese but released and made his way back to India after incredible difficulties, surviving several snowstorms. Now Thimayya had proof of Chinese incursion. When the Army presented this to the Government, Menon blew up. In Nehru’s presence, he told the senior officer making the presentation that he was “lapping up CIA propaganda.”

Per Dr.N.S.Rajaram, Wignall was not Thimayya’s only source. Shortly after the Chinese attack in 1962, he heard from General Thimayya that General Thimayya had deputed a young officer of the Madras Sappers (MEG) to Aksai Chin to investigate reports of Chinese intrusion who brought back reports of the Chinese incursion. But the public was not told of it simply to cover up Nehru’s blunders.

He was still trying to sell his Pancha Sheel and Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai to the Indian public.

Even today, Nehru’s family members exercise dictatorial control over the documents pertaining to this crucial period. Even documents in the National Archives are not available to scholars without permission from the Nehru-Gandhi family heirs. This is to protect his reputation from being damaged by the truth (But many of the same documents are available in the British Museum and Library in England).

The sorry catalog of blunders continued after Nehru’s death. In the Bangladesh war, India achieved one of the most decisive victories in modern history. More than 90,000 Pakistani soldiers were in Indian custody. The newly independent Bangladesh wanted to try these men as war criminals for their atrocities against the people of East Bengal. The Indian Government could have used this as a bargaining chip with Pakistan and settled the Kashmir problem once and for all. Instead, Indira Gandhi threw away this golden opportunity in exchange for a scrap of paper called the Shimla Agreement.

Thanks to this folly, Pakistan is more active than ever in Kashmir.

Additional Information:

On Nehru’s orders Indian soldiers fled Arunachal Pradesh then known as NEFA ( The North-East Frontier Agency ) leaving behind the Monpa tribe of Kameng Frontier Division to defend their country. The tribes resisted the Chinese, as much as they could and tales of resistance are untold about all those who died resisting the Chinese onslaught. In many places peace deals were struck over rice beer!

References:

tibetpolicy.net - Prof. Sachidananda Mohanty

(Prof. Sachidananda Mohanty is widely published in the areas of British, American and postcolonial studies. He is the author of acclaimed volumes, including one on Indo-US Educational Exchange [ Foreword by J.K.Galbraith].Formerly he was the Senior Academic Fellow at the American Studies Research Centre [ASRC] Hyderabad. He is an honorary consultant to Sri Aurobindo Society, Pondicherry.)

'Himalayan Blunder', a 1962 war memoir by Brigadier J. P. Dalvi

'Life and work of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel', by Dr Ravindra Kumar

Indian leaders on Tibet, a compilation of letters and speeches by the Central Tibetan Administration

byjus.com - Panchsheel Agreement

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at satyaagrahindia@gmail.com and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.

Related Articles

- How Nehru's Govt helped China in conquering Tibet and let go of it's centuries old friend

- On 16th Aug 1946, during Ramzan's 18th day, Direct Action Day aimed to provoke Muslims by mirroring Prophet Muhammad's victory at Badr, Gopal 'Patha', the Lion of Bengal, heroically saved Bengali Hindus & Calcutta from a planned genocide, altering history

- China attacked India just three years after PM Nehru reduced the defence expenditure by Rs 25 crores: Union Budget 1959

- Depth of Soviet penetration in Indian media is exposed through declassified CIA document from 2011

- Prophecies of Jogendra Nath Mandal getting real after seventy years of his return from Pakistan

- Calcutta Quran Petition: A petition to ban the Quran altogether was filed 36 years ago, even before Waseem Rizvi petitioned for removing 26 verses from Quran

- Ghost from the past: Unseen picture of Nehru voting in favour of partition of India goes viral

- Speech of Sardar Patel at Calcutta Maidan in 1948 busts the myth of ‘Muslims chose India’ and is relevant even today

- When Secular Nehru Opposed Restoration Of Somnath Temple - The Somnath Temple treachery

- Nehru's Himalayan Blunders which costed India dearly - Pre-Independence

- The untold story of Maharashtrian Brahmin genocide committed by Congress after Gandhi’s assassination in 1948

- Gandhi emphasized that he won't salute Indian National Flag if Charkha is replaced by Ashoka Chakra and wanted British flag added to it

- Operation Polo: When India annexed Hyderabad from the Nizam and Razakars, the suppression of Hindus and the role of Nehru

- Was Italian family of Sonia Gandhi involved in the Bofors scam: Papers long buried, questions that were never asked

- Father of the Nation! Absolutely not. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was not the father of the nation either officially or otherwise