Sanatan Articles

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

Satyaagrah

Written on

JOIN SATYAAGRAH SOCIAL MEDIA

A bit of History - An Indian Pilgrim (Netaji's Life and writings)

My father was born on the 28th May, 1860 and my mother in 1869. After passing the Matriculation (then called Entrance) Examination from the Albert School, Calcutta, he studied for some time at the St. Xavier’s College and the General Assembly’s Institution (now called Scottish Church College). He then went to Cuttack and graduated from the Ravenshaw College.

He returned to Calcutta to take his law degree and during this period came into close contact with the prominent personalities of the Brahmo Samaj, Brahmananda Keshav Chandra Sen, his brother Krishna Vihari Sen, and Umesh Chandra Dutt, Principal of the City College. He worked for a time as Lecturer in the Albert College, of which Krishna Vihari Sen was the Rector. In 1885 he went to Cuttack and joined the bar. The year 1901 saw him as the first non-official elected Chairman of the Cuttack Municipality.

By 1905 he became Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor. In 1912 he became a member of the Bengal Legislative Council and received the title of Rai Bahadur. In 1917, following some differences with the District Magistrate, he resigned the post of Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor and thirteen years later, in 1930, he gave up the title of Rai Bahadur as a protest against the repressive policy of the Government.

|

Besides being connected with public bodies like the Municipality and District Board, he took an active part in educational and social institutions like the Victoria School and Cuttack Union Club. He had extensive charities, and poor students came in for a regular share of them. Though the major portion of his charities went to Orissa, he did not forget his ancestral village, where he founded a charitable dispensary and library, named after his mother and father respectively. He was a regular visitor at the annual session of the Indian National Congress but he did not actively participate in politics, though he was a consistent supporter of Swadeshi.

After the commencement of the Non-co-operation Movement in 1921, he interested himself in the constructive activities of the Congress, Khadi and national education. He was all along of a religious bent of mind and received initiation twice, his first guru being a Shakta and the second a Vaishnava. For years he was the President of the local Theosophical Lodge. He had always a soft spot for the poorest of the poor and before his death he made provisions for his old servants and other dependents.

As mentioned in the first chapter, my mother belonged to the family of the Dutts of Hatkhola, a northern quarter of Calcutta. In the early days of British rule, the Dutts were one of those families in Calcutta who attained a great deal of prominence by virtue of their wealth and their ability to adapt themselves to the new political order. As a consequence they played a role among the neo-aristocracy of the day.

My mother’s grandfather, Kashi Nath Dutt, broke away from the family and moved to Baranagore, a small town about six miles to the north of Calcutta, built a palatial house for himself and settled down there. He was a very well-educated man, a voracious reader and a friend of the students. He held a high administrative post in the firm of Messrs Jardine, Skinner & Co., a British firm doing business in Calcutta.

Both my mother’s father, Ganganarayan Dutt, and grandfather had a reputation for being wise in selecting their sons-in-law. They were thereby able to make alliances with the leading families among the Calcutta aristocracy of the day. One of Kashi Nath Dutt’s sons-in-law was Sir Romesh Chandra Mitter who was the first Indian to be acting Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court. Another was Rai Bahadur Hari Vallabh Bose who had migrated to Cuttack before my father and as a lawyer had won a unique position for himself throughout the whole of Orissa.

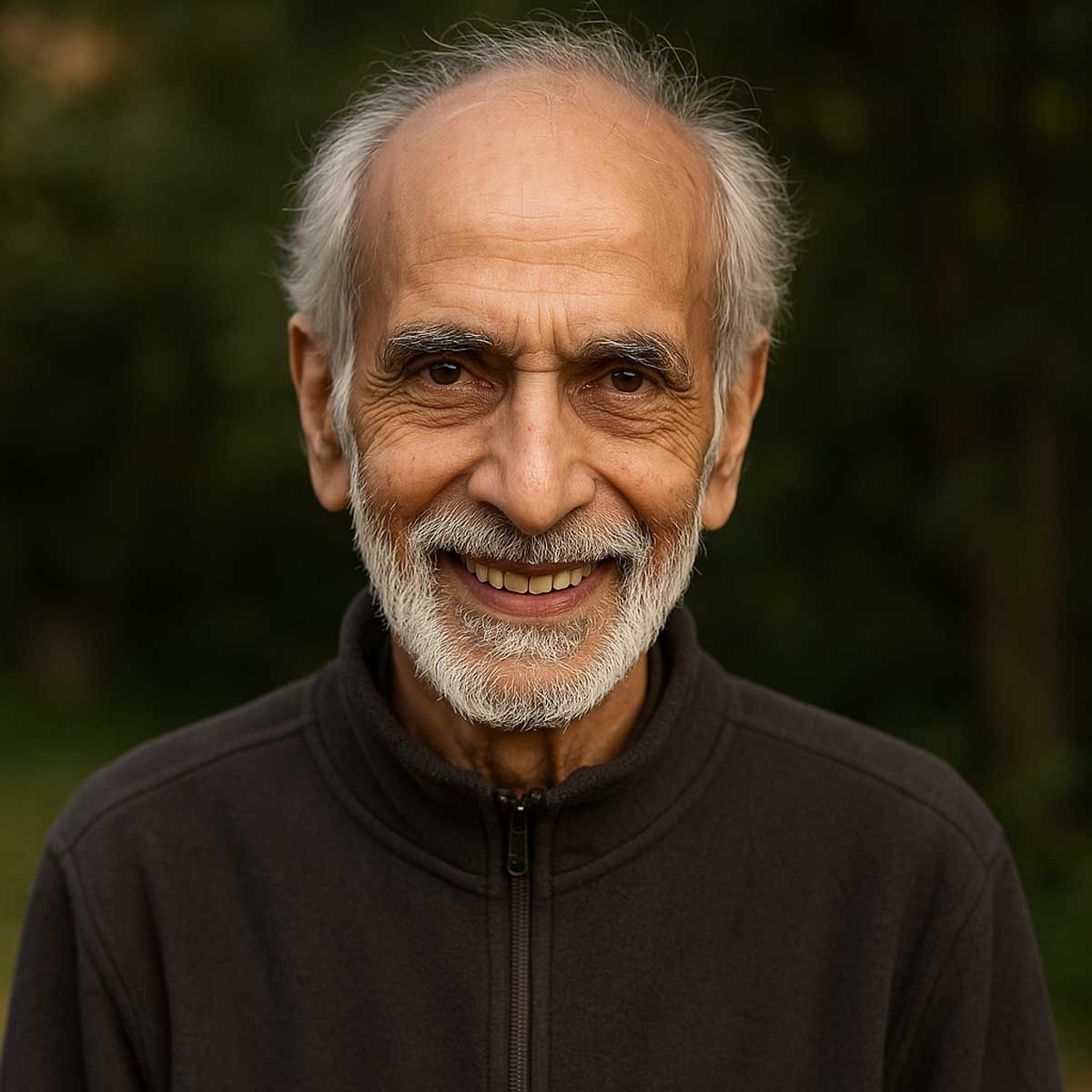

Photograph of Janakinath Bose displayed at Netaji Museum and Centre for Studies in Himalayan Languages Society Culture |

It is said of my maternal grandfather, Ganganarayan Dutt, that before he agreed to give my mother in marriage to my father, he put the latter through an examination and satisfied himself as to his intellectual ability. My mother was the eldest daughter. Her younger sisters were married successively to (the late) Barada Ch. Mitra, ICS, District and Sessions Judge, Mr Upendra Nath Bose of Benares City, (the late) Chandra Nath Ghosh, Subordinate Judge and (the late) Dr. JN Bose, younger brother of the late Rai Bahadur Chuni Lai Bose of Calcutta.

From the point of view of eugenics it is interesting to note that on my father’s side, large families were the exception and not the rule. On my mother’s side, the contrary seems to have been the case. Thus my maternal grandfather had nine sons and six daughters. Among his children, the daughters generally had large families—including my mother—but not the sons. My parents had eight sons and six daughters of whom nine—seven sons and two daughters—are still living. Among my sisters and brothers, some—but not the majority—have as many as eight or nine children, but it is not possible to say that the sisters are more prolific than the brothers or vice versa. It would be interesting to know if in a particular family the prolific strain adheres to one sex more than to the other. Perhaps eugenists could answer the question.

Prabhabati Bose née Dutta in her early age |

It requires a great deal of imagination now to picture the transformation that Indian society underwent as a result of political power passing into the hands of the British since the latter half of the eighteenth century. Yet an understanding of it is essential if we are to view in their proper perspective the kaleidoscopic changes that are going on in India today. Since Bengal was the first province to come under British rule, the resulting changes were more quickly visible there than elsewhere.

With the overthrow of the indigenous Government, the feudal aristocracy which was bound up with it naturally lost its importance. Its place was taken by another set of men. The Britishers had come into the country for purposes of trade and had later on found themselves called upon to rule. But it was not possible for a handful of them to carry on their trade or administration without the active co-operation of at least a section of the people.. At this juncture those who fell in line with the new political order and had sufficient ability and initiative to make the most of the new situation came to the fore as the aristocracy of the new age.

It is generally thought that for a long time under British rule Muslims did not play an important role, and several theories have been advanced to account for this. It is urged, for instance, that since, in provinces like Bengal, the rulers who were overthrown by the British were Muslims by religion, the Muslim community maintained for a long time an attitude of sullen animosity and non-cooperation towards the new rulers, their culture and their administration. On the other hand it is said that, prior to the establishment of British rule in India, the Muslim aristocracy had already grown thoroughly effete and worn out and that Islam did not at first take kindly to modern science and civilization. Consequently, it was but natural that under British rule the Muslims should suffer from a serious handicap and go under for the time being.

I am inclined, however, to think that in proportion to their numbers, and considering India as a whole, the Muslims have never ceased to play an important role in the public life of the country, whether before or under British rule—and that the distinction between Hindu and Muslim of which we hear so much nowadays is largely an artificial creation, a kind of Catholic-Protestant controversy in Ireland, in which our present-day rulers have had a hand. History will bear me out when I say that it is a misnomer to talk of Muslim rule when describing the political order in India prior to the advent of the British. Whether we talk of the Moghul Emperors at Delhi, or of the Muslim Kings of Bengal, we shall find that in either case the administration was run by Hindus and Muslims together, many of the prominent Cabinet Ministers and Generals being Hindus. Further, the consolidation of the Moghul Empire in India was effected with the help of Hindu commanders-in-chief. The Commander-in-chief of Nawab Sirajudowla, whom the British fought at Plassey in 1757 and defeated, was a Hindu, and the rebellion of 1857 against the British, in which Hindus and Moslems were found side by side, was fought under the flag of a Muslim, Bahadur Shah.

Be that as it may, it is a fact so far as Bengal is concerned, whatever the causes may be, most of the prominent personalities that arose soon after the British conquest were Hindus. The most outstanding of them was Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833) who founded the Brahmo Samaj in 1828. The dawn of the nineteenth century saw a new awakening in the land. This awakening was cultural and religious in character and the Brahmo Samaj was its spearhead. It could be likened to a combination of the Renaissance and Reformation. One aspect of it was national and conservative—standing for a revival of India’s culture and a reform of India’s religions. The other aspect of it was cosmopolitan and eclectic—seeking to assimilate what was good and useful in other cultures and religions. Ram Mohan was the visible embodiment of the new awakening and the herald of a new era in India’s history. His mantle fell successively on ‘Maharshi’ Devendranath Tagore (1818- 1905), father of the poet Rabindranath Tagore, and Brahmananda Keshav Chandra Sen (1838-1884) and the influence of the Brahmo Samaj grew from day to day.

There is no doubt that at one time the Brahmo Samaj focussed within itself all the progressive movements and tendencies in the country. From the very beginning the Samaj was influenced in its cultural outlook by Western science and thought, and when the newly established British Government was in doubt as to what its educational policy should be—whether it should promote indigenous culture exclusively or introduce Western culture—Raja Ram Mohan Roy took an unequivocal stand as the champion of Western culture. His ideas influenced Thomas Babington Macaulay when he wrote his famous Minute on Education and ultimately became the policy of the Government. With his prophetic vision, Ram Mohan had realised, long before any of his countrymen did, that India would have to assimilate Western science and thought if she wanted to come into her own once again.

The cultural awakening was not confined to the Brahmo Samaj, however. Even those who regarded the Brahmos as too heretical, revolutionary, or iconoclastic were keen about the revival of the indigenous culture of India. While the Brahmos and other progressive sections of the people replied to the challenge of the West by trying to assimilate all that was good in Western culture, the more orthodox circles responded by justifying whatever there was to be found in Hindu society and by trying to prove that all the discoveries and inventions of the West were known to the ancient sages of India. Thus the impact of the West roused even the orthodox circles from their self-complacency.

There was a great deal of literary activity among them and they produced able men like Sasadhar Tarkachuramani—but much of their energy was directed towards meeting the terrible onslaughts on Hindu religion coming from the Christian missionaries. In this there was common ground between the Brahmos and the orthodox Pundits, though in other matters there was no love lost between them. Out of the conflict between the old and the new, between the conservatives and the radicals, between the Brahmos and the Pundits, there emerged a new type— the noblest embodiment of which was Pundit Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar |

This new type of Indian stood for progress and for a synthesis of Eastern and Western culture and accepted generally the spirit of reform which was abroad, but refused to break away from Hindu society or to go too far in emulating the West, as the Brahmos were inclined to do at first. Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, for instance, was brought up as an orthodox Pundit, became the father of modern Bengali prose and a protagonist of Western science and culture, and was a great social reformer and philanthropist—but till the last, he stuck to the simple and austere life of an orthodox Pundit. He boldly advocated the remarriage of Hindu widows and incurred the wrath of the conservatives in doing so—but he based his arguments mainly on the fact that the ancient scriptures approved of such a custom.

The type which Iswar Chandra represented ultimately found its religious and philosophical expression in Ramakrishna Paramahansa (1834-1886) and his worthy disciple, Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). Swami Vivekananda died in 1902 and the religio-philosophical movement was continued through the personality of Arabindo Ghose (or Ghosh). Arabindo did not keep aloof from politics. On the contrary, he plunged into the thick of it, and by 1908 became one of the foremost political leaders. In him, spirituality was wedded to politics. Arabindo retired from politics in 1909 to devote himself exclusively to religion; but spirituality and politics continued to be associated together in the life of Lokamanya BG Tilak (1856-1920) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869).

This brief narrative will serve as a rough background to the contents of this book and will give some idea of the social environment which existed when my father was a student of the Albert School1 in Calcutta. Society was then dominated by a new aristocracy, which had grown up alongside of British rule, whom we should now call, in socialist parlance, the allies of British ‘Imperialism’. This aristocracy was composed roughly of three classes or professions—(1) landlords, (2) lawyers and civil servants and (3) merchant-princes. All of them were the creation of the British, their assistance being necessary for carrying out the policy of administration-cum-exploitation.

Arabindo Ghose |

The landlords who came into prominence under British rule were not the semi-independent or autonomous chiefs of the feudal age, but mere tax-collectors who were useful to a foreign Government in the matter of collecting land- revenue and who had to be rewarded for their loyalty during the Rebellion of 1857, when the existence of British rule hung by a thread.

Though the new aristocracy dominated contemporary society and, as a consequence, men like Maharaja Jatindra Mohan Tagore and Raja Benoy Krishna Deb Bahadur were regarded by the Government as the leaders of society, they had little in the way of intellectual or moral appeal. That appeal was exercised in my father’s youth by men like Keshav Chandra Sen and to some extent, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar. Wherever the former went, crowds followed him. He was, indeed, the hero of the hour. The spiritual fervour of his powerful orations raised the moral tone of society as a whole and of the rising generations in particular. Like other students, my father, too, came under his magic influence, and there was a time when he even thought of a formal conversion to Brahmoism. In any case, Keshav Chandra undoubtedly had an abiding influence on my father’s life and character. Years later, in far-off Cuttack, portraits of this great man would still adorn the walls of his house, and his relations with the local Brahmo Samaj continued to be cordial throughout his life.

Though there was a profound moral awakening among the people during the formative period of my father’s life, I am inclined to think that politically the country was still dead. It is significant that his heroes—Keshav Chandra and Iswar Chandra —though they were men of the highest moral stature, were by no means anti-Government or anti-British. The former used to state openly that he regarded the advent of the British as a divine dispensation. And the latter did not shun contact with the Government or with Britishers as a ‘non-co-operator’ today would, though the keynote of his character was an acute sense of independence and self-respect.

My father, likewise, though he had a high standard of morality, and influenced his family to that end, was not anti-Government. That was why he could accept the position of Government Pleader and Public Prosecutor, as well as a title from the Government. My father’s elder brother, Principal Devendra Nath Bose, belonged to the same type. He was a man of unimpeachable character, greatly loved and respected by his students for his intellectual and moral attainments, but he was a Government servant in the Education Department.

Likewise, before my father’s time it was possible for Bankim Chandra Chatterji (1838-1894) to compose the ‘Bande Mataram’ song and still continue in Government service. And DL Roy could be a magistrate in the service of the Government and yet compose national songs which inspired the people. All this could happen some decades ago, because that was an age of transition, probably an age of political immaturity. Since 1905, when the partition of Bengal was effected in the teeth of popular opposition and indignation, a sharpening of political consciousness has taken place, leading to inevitable friction between the people and the Government. People are nowadays more resentful of what the Government does and the Government in its turn is more suspicious of what the people say or write. The old order has changed, yielding place to new, and today it is no longer possible to separate morality from politics—to obey the dictates of morality and not land oneself in political trouble. The individual has to go through the experience of his race within the brief span of his own life, and I remember quite clearly that I too passed through the stage of what I may call non-political morality, when I thought that moral development was possible while steering clear of politics—while complacently giving unto Caesar what is Caesar’s. But now I am convinced that life is one whole. If we accept an idea, we have to give ourselves wholly to it and to allow it to transform our entire life. A light brought into a dark room will necessarily illuminate every portion of it.

References:

archive.org

Netaji: Collected Works Volume 1 - An Indian Pilgrim An Unfinished Autobiography - Subhas Chandra Bose (edited by Sisir Kumar Bose and Sugata Bose)

Support Us

Support Us

Satyagraha was born from the heart of our land, with an undying aim to unveil the true essence of Bharat. It seeks to illuminate the hidden tales of our valiant freedom fighters and the rich chronicles that haven't yet sung their complete melody in the mainstream.

While platforms like NDTV and 'The Wire' effortlessly garner funds under the banner of safeguarding democracy, we at Satyagraha walk a different path. Our strength and resonance come from you. In this journey to weave a stronger Bharat, every little contribution amplifies our voice. Let's come together, contribute as you can, and champion the true spirit of our nation.

|  |  |

| ICICI Bank of Satyaagrah | Razorpay Bank of Satyaagrah | PayPal Bank of Satyaagrah - For International Payments |

If all above doesn't work, then try the LINK below:

Please share the article on other platforms

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text. The website also frequently uses non-commercial images for representational purposes only in line with the article. We are not responsible for the authenticity of such images. If some images have a copyright issue, we request the person/entity to contact us at satyaagrahindia@gmail.com and we will take the necessary actions to resolve the issue.